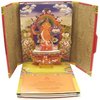

Buddhist Altar

Buddhist Altars

The shrine is placed in the temple or home as a place of worship to the Buddha, the Law of the Universe, etc. Scrolls (honzon) or statues are placed in the Fut Taahn and prayed to morning and evening. Zen/Chan Buddhists also mediate before the Fut Taahn.

The original design for the Fut Taahn began in India, where people built altars the size of skyscrapers as an offering-place to the Buddha. When Buddhism came to China and Korea , statues of the Buddha were placed on pedestals or platforms. The Chinese and Koreans built walls and doors around the statues to shield them from the weather. They could then safely offer their prayers, incense, etc. to the statue or scroll without it falling and breaking.

When the Japanese finally welcomed Buddhism after many years of Shintoism, they took in the religion along with the Fut Taahn/j. Butsudan. As many new Buddhist sects came into being, the altar was placed in many temples. The Japanese took the plain walls and doors of the mainland shrines and elaborately embellished them, and the this altar became the focal point of every temple. As time went on, people began installing this type of altar into their homes. Elaborite Altars can be extremely expensive.

The arrangement and types of items in and around this altar type can vary depending on the sect. A Fut Taahn usually houses a statue or painting of the Buddha or a Buddhist deity, though embroidered scrolls containing a mantric or sutric text are also common. Other auxiliary items often found near the butsudan include tea, water and food (usually fruits or rice), an incense burner, candles, flowers, hanging lamps and evergreens. A Rin Gong or "singing bowl" often accompanies the butsudan, which can be rung during liturgy or recitation of prayers. Members of some Buddhist sects place ihai or tablets engraved with the names of deceased family members within or next to the butsudan. Other Buddhist sects, such as jodo shinshu usually do not have these. The butsudan is typically placed upon a larger cabinet in which are kept important family documents and certificates.

The butsudan is commonly seen as an essential part in the life of a traditional Japanese family as it is the centre of spiritual faith within the household, especially in dealing with the deaths of family members or reflecting on the lives of ancestors. This is especially true in many rural villages, where it is common for more than 90% of households to possess a butsudan, to be contrasted with urban and suburban areas, where the rate of possession can drop down to below 60%

Sample Photo 6